Join host Christopher Smit for the first episode of the DisTopia Podcast. His guest is activist and writer Mike Ervin who has been a leader in the disability civil rights movement since the 1980s.

Episode 1: Mike Ervin

[Rock music playing]

Woman’s Voice: From DisArt Productions, it’s DisTopia.

[Rock music continues to play in the background]

Christopher (Chris) Smit = CS (Interviewer/Host)

CS: Hi folks, welcome to the DisTopia Podcast, where we attempt to look at disability culture and cultural differences of all types from the inside out. I’m your host, Christopher Smit. On today’s episode, an intimate conversation with activist and writer Mike Ervin. Ervin gained notoriety during the 1980s as his group “Jerry’s orphans” took on Jerry Lewis and the almighty muscular dystrophy telethon. It’s really a great conversation, we hope you enjoy it. But first, let’s get oriented…

[Rock Music plays louder and then fades out]

CS: Okay, so I don’t know you, and you don’t know me at least yet. But we’re hoping that changes as we spend some time together in DisTopia. But for now, I want to share just a couple of thoughts about the podcast, about me, and about what we’re trying to do here.

Podcasts have done a great job in the last five years of opening up spaces for, what a lot of folks call, niche (nitch) markets or niche (neesh spoken as a question) markets. Markets have moved away then from being very very broad to being very narrow. That’s why we have podcasts and blogs about people who love pinewood derby cars or for people who love to make grilled cheese, and (and this is where we get excited) there’s now a possibility for podcasts and all media that might actually be targeted at disabled people specifically. Listen up advertisers, it’s your time to target us. You can finally make that big cripple money. Yeah, imagine that… Media being made specifically, being targeted specifically at people who deal with being different on an everyday basis.

Now, when we didn’t have blogging and social networking and podcasts, most of us who went to the movie theaters or watched TV or participated in pop culture in any way never really saw ourselves reflected back. For me, a disabled kid growing up in a suburb of Chicago, there was really no part for me to play in the adventures on the big or small screen. No sitcoms had disabled people and none of the movies did either. And, well, if they did…If there was a disabled character let’s not really think of those folks as good positive role models. Right, these were the killers in a James Bond movie, or the weirdos, or the inspirational, or the misfits. All of them are misfits. And honestly, I didn’t feel like a misfit. I was a normal kid. I had friends. I had girlfriends. I played in rock bands. I smoked cigarettes behind my parent’s house. I had access to good healthcare. Good health insurance through my parents. I had technology. I had money that could pay for wheelchairs to get me around and I had this sense of humor that came from my folks. Quite honestly, it made me easy to be around, people weren’t so freaked out by me. I had opportunities.

My parents were amazing people. They always told me that my muscular dystrophy shouldn’t stop me from doing anything… So it rarely did… Until later in life when things got real. It really wasn’t until my late 20s when I was discriminated against for the first time that I began to realize, and this is strange…That I began to realize that I was a disabled person. Isn’t that strange? And from that moment on, I’ve been diving deep into disability culture… I’ve been looking for allies, I’ve been searching for answers about my identity, I’ve been writing articles and books and blogposts and speaking to audiences about disability and art and disability and culture. But what it all boils down to is I want people to think with me about what it really means to live the disabled life.

And so the folks I work with at DisArt, the organization that puts this podcast out. We’re putting it out there as a way to continue that work… To talk about identity…To talk about culture…To talk about disability and reality. Putting it plainly… Most of the world freaks out when it comes to disability. People are scared by it, they’re intimidated by it. Many people are angry at. And that makes the world that us disabled people live in difficult. So, what we’re trying to do here is create a space for conversation about disability as it is really experienced. So, can a podcast change the world? Maybe. We hope so. We don’t know for sure but we’d like to give it a shot and we need you to be a part of it. Tells us your stories. Tell us what you’re experiencing and hopefully together we can find some clarity. Okay, let’s move on.

[Music plays briefly]

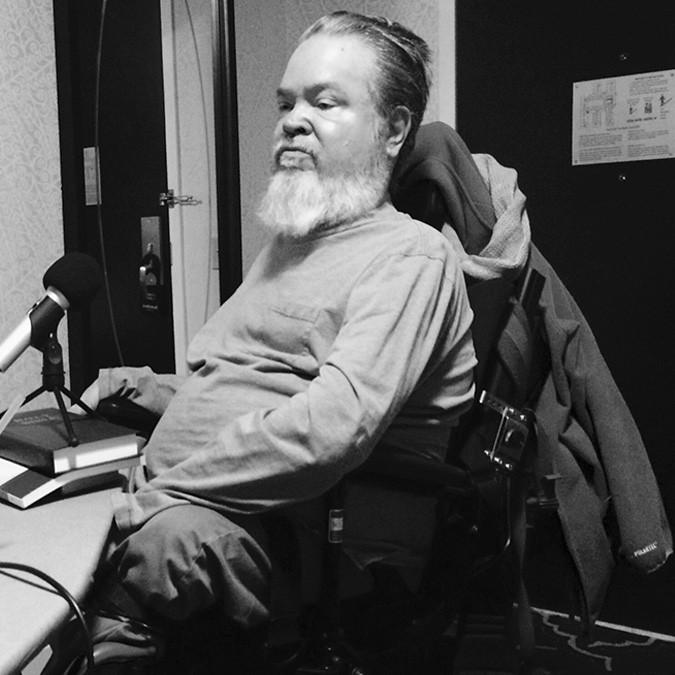

On today’s episode an intimate conversation with activist and writer Mike Ervin. Mike Is one of the original troubadours of disability rights activism… Working out of his home city in Chicago during the 1980s he helped organize a group of disability activists to take on the powerful Chicago transit Authority…And what did they want? Accessible buses. They wanted to be able to get around, to get to their work, get to their doctor’s appointments, get to their life. And they did anything they could to get their message out including chaining themselves to City Hall, storming CTA meetings, and parking their wheelchairs in front of buses. And it worked. Today, 100% of Chicago buses and trains are said to be accessible. Irvin made that happen with an organization called ADAPT, which he is still active in. ADAPT fight for the rights of all disabled people to gain independence through transportation, accessible and affordable housing, and fights for legislation that makes it easier for people to live on their own, in their own homes and pay for their own caregivers rather than get stuck in nursing homes. Mike is also an active playwright and writer. In 1992 he started the Victory Gardens Access Project, a collective of disabled actors and playwrights, all looking to get the disabled story on Chicago Theatre stages. Of all his accolades, however, the one he is perhaps most known for is his group “Jerry’s Orphans” which took on Jerry Lewis and his muscular dystrophy telethon for what the group saw as paternalistic pity partying. In 2015 MDA announced that it would no longer have this telethon… And I think it’s fair to say that Mike Ervin played an important cultural role in getting that to happen. Mike fights every day for the lives of disabled people. His blog Smart Ass Cripple is his continuous love letter to the disabled world, a collection of witty and biting proclamations about why disabled folks need equality.

[Music plays briefly]

I interviewed Mike Ervin at the Palmer House, a really old classy hotel in Downtown Chicago. I was staying there at the time and Mike came up to our room and there wasn’t a table big enough for our equipment so we set up an ironing board…always figuring out the tactics of a crippled life. We put his microphone at one end and my microphone at the other and just started talking. I really think we got some important stuff on tape not only about Mike and his life but also about the disability Rights Movement in Chicago, the Jerry’s Orphan’s Movement that Mike was a part of, and, well, you know what, we just got real. Real information. Real stories about living the disabled life so I hope you enjoy it.

[Music plays briefly]

Chris Smit = CS (interviewer)

Mike Ervin = ME (interviewee)

CS: How long have you been in Chicago?

ME: How long have I lived here?

CS: Yeah, I mean you’ve been downtown for a long time?

ME: Right where I live now, 21 years.

CS: And you’re right in the heart of it.

ME: Pretty much. Just a little in the shadow of downtown I call it. It’s a neighborhood called Printers Row. They call it that because it is old, well by Chicago standards, it’s old buildings; early 1900s late 1800s. Our building was built in 1911.

CS: 1911! And the building has been accessible those many years?

ME: Well, it’s accidental accessible. There’s no step out in front and there’s three elevators. If you move in, you have to adjust the bathrooms. Other than that, it’s pretty good.

CS: You use the buses all the time, then, or not that much anymore?

ME: I use them when weather permits and where I’m going permits. In winter I end up using my own vehicle a lot. There’s buses, there’s cabs, there’s trains. So, (I’m) multimodal, I guess.

CS: Do you have a sense when you’re on those buses that you helped make them accessible?

ME: It’s funny sometimes when I see someone waiting for one especially if they’re young. And I think, “Boy, I wonder if you have any idea what it took to make that bus accessible and if I came up to you right now and told you you’d probably think I was some wacky old man talking out of his ass and you probably wouldn’t believe me.” It’s kind of good to know that it’s such a crazy story.

CS: It makes me think of that sort of intergenerational thing. Even for myself I’ve spent only the last 10 years really digging deep into that history and I think that’s a pretty interesting dilemma in our culture, don’t you think? I mean, this idea that we have generation gap in bringing kids up in the schools. Are they getting that history? I’m always worried about that.

ME: Yeah, well, they’re not going to get in school, that’s for sure. They’re going to get it from us and from each other, I guess. And probably a lot of them don’t and it’s too bad because they’re going to get stung by it sooner or later.

CS: It’s interesting isn’t it that the ADA Legacy Bus that’s going around with Tom Olin and we’ve spent a lot of time with Tom and he was telling us that most of his photographs use to be in those Weekly Readers.

ME: (laughs)

CS: Right, that’s crazy. Those were distributed all over the country.

ME: Wow!

CS: And that is a really interesting part of that history. So, kids are looking at current news and “bam” there’s a picture of you or somebody else chained to a bus…

ME: (laughs)

CS: …and they’re like “what the fuck” and, you know, that’s just crazy. But that’s not happening either, right. The internet, I suppose, takes over that. I hope that those stories are getting out there.

ME: The internet probably helps, but I think that more young people are getting it than I feared.

CS: Yeah, sure, sure.

ME: And I think that it’s inevitable that there’ll always be a certain amount of activists; a certain amount of people who relate and a certain amount who don’t. And they’ll probably have many of the same stories about how silly it was. They’ll probably say, “Can you believe there was a day when we flew on airplanes and we had to give up our wheelchairs?” And….”Man that must be crazy, the things we do now and they have to do.”

CS: I hope that’s the case, man.

ME: (laughs)

CS: Isn’t that like the worst? You travel, right…

ME: Oh yeah

CS: …and it’s like, it’s hell. Right? Everybody I know who’s in a chair has that hell story, right, right?

ME: (laughs) Oh yeah, it got broke somehow.

CS: It got broke or they drop your chair or they bend your chair.

With Smart Ass Cripple, your blog, do you have a sense of your readership? Do you know who’s reading or how many people are reading?

ME: You get stats on them. How accurate they are, I don’t know. I don’t think they count the bots and the ones that just come by that aren’t really reading and I don’t know if they capture everyone who’s reading. It goes up and down. When Roger Ebert was tweeting obviously I had very high readership and Roger was very good to me. I don’t know who exactly is reading but every once in awhile I find that it landed in a place that I didn’t expect and something will come out of it. Like one time I got contacted by a New York Times editor asking if I wanted to write an Op Ed; so I did and then that got seen. So, that’s the thing about the internet. You just never know where something’s going to land and they also have something on the stats to show you what countries things come from. There’s Saudi Arabia. I wonder who’s reading Smart Ass Cripple in Saudi Arabia.

CS and ME: (Laughter)

CS: I love that. I love the idea of that. I mean, that’s what activism has turned into, right? Digital activism. You’re right. There is that sort of happenstance to it and you never know what’s going to pop in.

CS: So, you grew up in Urbana, right?

ME: No, here in Chicago.

CS: Oh were you in Chicago?

ME: Yeah, on the Southwest side over by Midway Airport.

CS: What’s life like back then for you? Siblings? Your house? Can you think of that environment still?

ME: Actually, I was born in Germany on an Army base. My dad was in the Army, but I don’t remember any of that because we came back when I was about a year old. But I was born there. Yeah, the house we lived in on the Southwest side was a decent middle class two bedroom house with an attic. It was just my sister and I. She had the same disability. She was about a year and a half older. She died about 2011. We got along very well. Toward the end of her life she became more of a Christian Republican and as long as we ignored that stuff we could still get along.

CS: (laughs)

ME: Fortunately, we had enough other things to talk about. (laughs) But we went to a segregated school called Walter Christopher School. If you had anything resembling a disability, they sent you there. The two best examples I can think of is…it was more like, it wasn’t if you were disabled, it was if you were freaky or if you were going to scare somebody they would send you there. And that was kind of how they defined disability. Well, some examples…there was a kid who had false legs and you wouldn’t even know he had false legs until he ran because they would make noise. But, other than that, when he walked and everything you couldn’t tell. There were kids that had, and I wrote about this in Smart Ass once, something called Slipped Epiphysis where they would come in and they would be walking on crutches and they’d have a strap attached to their belt on the back of their pants and then the strap was hooked to the heel of their shoe and they’d literally walk around with one leg tied behind their back on crutches. It was some kind of hip injury that I guess now you can cure pretty easy and it seemed like for about a year or so they’d be hobbling around. So, for that year they sent them to that cripple school and then they’d get better and then they’d send them back out again.

CS: So, what’s that memory like? I, myself, was what they called mainstreamed and so I went to school..this was in the mid-80s so I’m right alongside temporarily able-bodied kids and in that sort of system. But, did you have a sense of the segregation of it?

ME: Yeah, I did. The full impact of it didn’t hit me until later. Yeah, well, there was another girl who literally had a fake nose. She had no nose and apparently somebody made her a nose. It looked like clay or something. It was really weird and it was darker than her skin and it was glued on literally and sometimes it would fall off and she’d have to go to the nurse and get it glued back on again. Other than that she didn’t have any disability at all.

CS: So it’s a freak show?!

ME: Yeah, basically if you were a freak, they’d sent you there. When I look back on it I could see where I was emotionally segregated. I felt pushed away and being different didn’t feel like a good thing and usually being different is suppose to be good but as a kid it didn’t. And why I didn’t understand until later when I could articulate when they were basically saying you’re a bad different, a freakish different. But the good thing about it was the neighborhood I grew up in was very lily white and racist and I didn’t get to go to school in that neighborhood and I think the school we went to was about 80% not white and so I think it was good. It was probably good in that sense that it separated me from that environment and kept me away from having those kinds of attitudes although I didn’t have them much in my house either so I think I would have avoided them anyway. But being sent away like that and sent to the “freak show”…I’m also kind of glad..I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone and I don’t think the policies should force people into that, but I’m kind of glad that I was sent to the “freak show” because I think it also gave me kind of a “freak pride” too which I have these days and a sympathy for people that are called freaks. I spend a lot of time thinking about what that means and why people get called that and what they should do with it when they are called that. I don’t know that I would have had that perspective otherwise so I guess in that case it was good.

CS: And so you’re able to articulate that now at this end of your life; on this side of that experience. My brother is a disabled guy as well and because we were mainstreamed we joke about not being disabled until we were in our 30s.

ME: (laughter)

CS: Do you know what I mean? Just sort of realizing one day when my wife and I moved to Iowa and we felt discriminated against for the first time in my 20s and I thought, “Holy shit. Like this, this is new to me” because I, for whatever reason was lucky and blessed enough to be in this very experimental program in Downer’s Grove. A lot of money in Downer’s Grove; lot of sort of experimental programs and funding where the disability community of students was, you know, like we were together sometimes during the day but for most of the day we were pretty independent. And so it’s interesting to you hear you say that that really formulated your identity even early on where, in some ways, I’m still going through that.

ME: Really? Well, so am I. So is everybody. (laughs)

CS: I suppose. It’s ongoing, right? Yeah.

[Music plays briefly]

CS: So your sister and you…you got the same condition. Tell me about your parents. Who were they?

ME: My mom was quite strong. The image I have is us both in wheelchairs and her pushing one with one hand and reaching back and grabbing the armrest of the other and pulling the other from behind. And we often laughed about what we must have looked like going down the street like that.

CS: Fucking freak parade…

ME: And we had a dog too so sometimes there would be a dog tied to a wheelchair and it must have looked pretty funny especially back then. But her attitude was always …It wasn’t an activist attitude, it wasn’t like she was trying to prove anything like, “My kids are going to go to college, dammit and they’re going to do this and that.” It was almost like she didn’t know any better. Like she didn’t think anybody would think otherwise. You know your kids are smart and capable so they go to college. Why not? So I think by the time that we got old enough to realize that other people might not think so we’d already been pretty much indoctrinated with the attitude that we didn’t have to give into that and I think that helped a lot. And she was very supportive. For instance, after we graduated from Walter Christopher we went to an even more segregated place where we actually lived in called the Illinois Children’s Hospital School. (laughs)

CS: Oh my gosh. How long were you there?

ME: That’s where I have my high school diploma from. I can’t imagine that Southern Illinois accepted me with a diploma from the Illinois Children’s Hospital School. But we went there. My sister had really long hair. She liked having long hair and right after we showed up, the house parent (it’s what they call the workers there). One of them told us, “We’re not taking care of this long hair. We’re going to cut it off” which really hurt my sister and my mother one day brought her back and measured her hair and said, “When I see her every weekend, I’m measuring her hair and it better not be any shorter.” So they didn’t cut her hair off. So things like that. My mom did a lot for us.

CS: As you look back now however many years ago that is. Was that 30 years ago?

ME: We started there in ’69.

CS: Are they all dark memories or are they good memories too?

ME: Dark but comically dark. (laughs)

CS: I hope, God, that we all get to get to that point where it’s humorous. But not all dark, you said? There’s some fun?

ME: It’s a lot of good people caught in a really crappy system and it’s hard to escape and good people either find a way to make the best of it or get out. And there were people there that were important to me as an adolescent and did good by me and there were some people that I’m glad I’ll… (laughs)

CS: …never see again

ME: …to be rid of, yeah, that I’ll never see again. But the whole system is just a dumping ground. It’s the opposite of when we send folks who don’t have disabilities away to a separate school it’s because we’re giving them the best. And with disabilities it’s kind of the opposite; we’re dumping them off in the corner and giving them the bare basics so we don’t have to deal with them.

CS: I knew a lot of guys that went through that and I would go to camp with them. You went to MD (muscular dystrophy) camp?

ME: Oh yeah.

CS: Yeah, in fact, I think that’s probably where my brother met you for the first time. Right? Did you go to Hastings?

ME: Yeah, I went up to the ones in Northern Illinois.

CS: Do you have memories of that stuff?

ME: Oh yeah, I still have friends that went there.

CS: For me, camp was fucking wild.

ME: (laughs)

CS: Was it that way for you?

ME: Yeah, I had fun. I looked forward to going. I was also frustrated when I got older about the uptightness of the people in charge and the fact that anybody with a disability could never be anything other than a camper. That stuff started bothering me after awhile. But we always had fun and we ended up getting kicked out.

CS: You got kicked out?

ME: Yeah. I was really proud of that because it was really hard to get kicked out as a camper. (laughs)

CS: Can you talk to me about what was going on?

ME: I was kind of disappointed actually because my friends and I use to fantasize about what it would take to get kicked out

CS: (laughs)

ME: …and all these wild scenarios. And really ended up just being caught drinking. That’s all it was. (laughs)

CS: We’re talking about muscular dystrophy camp, right, so MDA camp and was that an MDA camp? Yeah, it was. I went to one in Michigan. When I think back to my camp experiences, I think, all right, I had my first cigarette at camp, I got drunk the first time at camp, saw my first breast at camp.

ME: (laughs) Oh wow…

CS: Yeah. I mean it was like this fantasy camp in some ways.

(CS and ME laugh)

You know that Make a Wish Foundation? It was sort of that ideology. The counselors were all these college students who were like, “We’re going to give them the best week of their life.”

ME: They won’t be here next year….(laughs)

CS: Yeah, yeah, exactly. There was a lot of that too.

ME: And you come back, “you’re back?!”

(CS and ME laugh)

CS: You made it! All right! Woo Hoo. It’s sort of like this real “break free moment”. So then you ended up at Southern Illinois, then? What’d you do at college? What was that about? What was that like for you?

ME: Well, it was the first non-segregated place I went to and the options were pretty limited at the time especially when you come from The Illinois Children’s Hospital School. You’re pretty much guaranteed you’re not going to the Ivy League and I didn’t have the best grade point basically because I didn’t really care that much and I didn’t apply myself. I mean, I did okay but it wasn’t like I was valedictorian or anything although we only had 9 people in a graduating class so it wouldn’t have been hard to be valedictorian. (laughs)

CS: I was going to say, you could probably get that. (laughs)

ME: So we went there. But also what was accessible at the time was limited. At the University of Illinois they literally would not take you if you couldn’t physically take care of yourself which would be illegal as hell now, fortunately. It’s another thing young people might look back and laugh, fortunately. But Southern Illinois was about it but that was okay with me because it was far away but not too far away and they had a good journalism program and that’s what I was interested in anyway. So, I went there and lived in a dorm for two years and lived off campus for two years and got out and got a job at a newspaper writing obituaries. (laughs)

CS: Wow, really. So, you’re with caregivers? Guys you knew or guys you just hire?

ME: Guys I’d hire. Part of the voc rehab sending you to school was they would give you $8 a day to pay someone to help you.

CS: $8 a day. Wow.

ME: Which in 1974 was okay. I mean it was pretty bad then but at least the college student would take that in 1974 and so that’s what I did.

CS: So you did journalism. Did you have the sort of cliché moments of enlightenment in college where you sort began to see the larger structures of life?

ME: Yeah, more of a politicizing…just seeing more and studying more, having a better education than the very very limited curriculum at the hospital school. The hospital school I call it the Sam Houston Institute of Technology. That’s my name for it because it spells SHIT.

CS: (Laughs emphatically)

ME: That’s what I call it now so at Sam Houston it was a very limited curriculum so, yeah, just getting there and learning more and being on my own. Although like I said, my mother was never really smothering or obstructionist and so it wasn’t that radical of an experience. But just having your own household and everything.

CS: When I went to college it was the first time I had ever lived on my own and we hired people to take care of me. Two guys. Sophomores. Two sophomores in college. I never met them. I talked to them on the phone. My parents drove me to Michigan, dropped me off, said good-bye, and there I was.

ME: Wow.

CS: Never had had any other caregiver but my mom and dad. I mean, we didn’t hire caregivers. This was a middle class family. We didn’t have extra money to hire people and then all of a sudden there I am with these two guys. It was terrifying. Did you have caregivers growing up outside the family?

ME: In the S-H-I-T place, you know, we had various people helping us out but they weren’t of our choosing, of course. And that was, of course, the main difference of being on my own was I finally had people of my choosing. The importance of that became very clear to me very quick and very important to me and I learned a lot about how to manage those things and who makes a good one and who makes a bad one.

CS: Yeah, God. I mean that could be the focus of a whole other series.

[Music plays briefly]

CS: How aware are you of Ed Roberts, Berkeley, you know during that time? Are you aware of that at all?

ME: No, no. When I look back at the 504 sit in of ’77, I was in college at the time and it wasn’t until many years later that I even heard of that and I feel almost kind of silly that I didn’t really understand it. But I had a consciousness of how to take care of myself, how to make sure that I got what I needed and then if there was somebody who happened to be sitting next to me that could benefit from what I got for myself, then that was great. But I didn’t really start to think about the larger picture, I mean, I moved back here after college. I lived with my mom for about six years until I moved out. The mayor’s office ran a transportation service which you could call during the day to take you to the doctor or something like that so I learned how to use that. Like I’d say, “I’m going to the doctor” and have them drop me off downtown and go somewhere else…

CS: Yeah, yeah, yeah (laughing)

ME: …and come back, “Yeah, I just came back from the doctor” and that kind of thing. I learned how to do that. But in 1983 a guy named Kent Jones who was in his 50s at the time was a local guy who had MS (Multiple Sclerosis) and he went off to Denver to the first ADAPT action. And he comes back and he’s like Marco Polo telling us grand tales of the orient and everything. You know, “I went there were buses and you could get on them and you could go anywhere”

CS: (laughs)

ME: …and we were all like, “Come on…”. “No really, and we can have that here too.” So, at the time we just had the door to door service and I was calling in advance and break a busy signal and 9 to 5 on weekends. And they might not show up and you know all the problems that come with a door to door service. And I was starting to get sick of that because I wanted to go places on my own. I don’t drive and we always had a van and I’d run places with my mother and she let my friends drive so I had a fair amount of mobility but, you know, sometimes I might just wanted to go somewhere by myself. And the whole idea of the lifts on buses all of a sudden became very clear to me and I thought, “Wow! This is the answer.” And I also, again, felt kind of stupid that I had a bus going down my street my whole life as a kid and it never once occurred to me, “Why, why can’t I get on there?” Never thought about it. But anyway, I thought, well, now’s the time to do something about it. I also just happened to be reading the book Rules for Radicals at the time by Saul Alinsky and the whole thing fit together for me really well what he was talking about and what was going on with ADAPT. So, that’s when I started thinking about the bigger picture and how doing things like just making sure I got somewhere between 10 and 2 in the afternoon during the week was never going to be enough and the only way it was going to get better was if we made a big change for a lot of people instead of just a little change for me.

CS: And that’s what year, then? What year does that start revving up in Chicago?

ME: We did our first action in April of ’84.

CS: Okay. You say “we”, that’s ADAPT?

ME: Chicago ADAPT, yeah. We went to a CTA board meeting and we made noise and we presented demands and they fought us for five years and spent millions of dollars and eventually met all of our demands. (laughs)

CS: Yeah, yeah, yeah, right. Now how did ADAPT get together here in Chicago? I mean, you’re one of the cornerstones of that?

ME: Kent went away and he came back and people like Susan, the old timers that are still around…

CS: Susan Nussbaum, yeah…

ME: Yeah, Susan Nussbaum. We all met in this woman’s kitchen one day and he told us about how he was married to a woman named Anna at the time who was also involved in ADAPT. And there was maybe just ten of us but it was because of…I mean you mentioned Ed Roberts. It was because ten years before that, Ed Roberts started a movement which led to the CILs (Centers for Independent Living) which led to money for CILs which led to Access Living which was a place where we all found each other and from there we were able to get together. So without all that happened before, whether we would have ever all met each other or not, who knows.

CS: Yeah, yeah. So Access Living then becomes this sort of hub in some ways. This sort of famous hub of activism.

ME: Yeah, yeah.

CS: A place where we all met each other and a place where we’d all show up and bitch about how our ride was an hour late. Or, we’d actually meet each on these buses. There’s a guy name Rene Luna who is still active in Chicago and that’s how we met. We were both waiting on a para transit bus on day and bitching about how we didn’t like it and I told him about ADAPT and he joined up. So, they shouldn’t have done that; they should have kept us segregated.

CS: Yeah right, exactly. (laughs) Well, Jerry Lewis finds you, right,…

ME: (laughs)

CS: …somewhere along the way which is such a common…actually, it’s more common than I even imagined; a common narrative for us who have muscular dystrophy that, somewhere along the way, Jerry Lewis or MDA gets ahold of us and loves our faces and cuteness and whatever. What year?…that happens for you quite young, right?

ME: Yeah, it was probably ’63, ’62, something like that. But it was somewhere along there. But it was just local, they didn’t have the national telethon at the time. But I remember doing the things that go with that; kind of just being a prop. You know, wave, smile and I remember not feeling moved about it too much one way or the other. Not feeling like, “Wow, I’m a star” or “Wow, I’m being really degraded”. But I just thought it was something to do like going to church; they tell you to do it so you do it. And the same way I felt about church; it didn’t move me one way or the other. Then I started getting older. When you’re a teenager you don’t want to be called a kid anymore. And I started to rebel against that and the reaction that I got was so harsh. It almost made me want to do it more because it was a ridiculous response to an objection.

CS: What did they say? Was your mom behind you in that decision to say, “Look, I’m going to step back”?

ME: She always was. She’d protest with us. How it happened with the Jerry’s Orphans was…you know, we’d always objected to it but we still went to camp and we even did the telethon once before we started objecting to it. But I never really did much about it other than complain. But in 1990, you know, they use to have the Parade magazine and Jerry Lewis had the cover every year. And that year he had a particularly harsh piece about “If I had muscular dystrophy” and rather than go into details, people should just look it up. But it was really insulting. He put himself in the 1st person as somebody with muscular dystrophy and it was as if he pretended he was black and talked about how much he loved ribs and things like that, you know. That was kind of the level it was in. Unfortunately, I read it like the day after the telethon that year and then I thought…Well, so I took it home and I showed it to Anna and I showed it to my mom and my sister and they all had pretty much the same reaction and so we decided to protest the next year and called ourselves Jerry’s Orphans. The two times when I felt most physically threatened…I’ve been in a lot of protests where we blocked doors, kept angry smokers from leaving buildings, and things like that. But the two times I felt most physically threatened were at the two anti-telethon protests and one was at a hotel where a security guard just started grabbing everybody that wasn’t in a wheelchair and he grabbed the blind guy and just wrestled him out the door even though the guy was blind and he grabbed another guy who had Hemophilia and just wrestled him out the door and later he lifted his shirt and showed me the handprint that he had left on his chest from being manhandled. And then there was the other time when I was only about…maybe seven, eight years ago when Jerry Lewis came to the Chicago Public Library to plug a book and he was in an auditorium with 500 people and about five or ten of us showed up and we didn’t say anything for awhile and then after about 10 minutes into the talk…

CS: …So they let you in…

ME: Yeah they did. I was shocked. I was shocked that they did. And we had some people who weren’t disabled standing in the crowd just in case they didn’t let us in. But they did and about ten minutes into the talk we just started reciting stuff, stupid shit that he had said like, “If you are crippled and don’t want to be pitied then stay in your house”. We just had a list of quotations and we just started reciting them.

CS: Just out loud?

ME: Kind of in a Row Row Row Your Boat type fashion like one guy start and the other would join in and eventually he just said, “Those sons of bitches,” and stormed off. But the place was full of Jerry Lewis fans and I thought that they were literally grabbing some of the people that stood up in the audience because they thought, “Well, you’re not crippled. I can grab you” and pushing them. And the cops literally separated from the crowd with the glass door in the way. And I remember one guy said to me “I’ll slap that grin off your face” and another guy said, “There’s a reason God does what he does, Pig.” So those were the two times when I actually felt physically threatened. But that’s how people reacted when you challenged what Jerry Lewis was all about and it really tells me not only how sacred that whole charity thing is but what a huge fear that that whole thing covers up because the reason people are so attached to it is because they don’t want to deal with the larger questions and they just sort of buy it away with charity. And when you take that option away from them and force them to deal with what do we do with disabled folks in our presence it really angers them. I still don’t quite know why, but I certainly see that it angers them.

CS: Well, it critiques the narrative, right? It critiques the narrative that everybody’s bought into and everybody’s use to and so if the cripple isn’t pliant and smiling and innocent and whatever, then you shatter a worldview that’s been pretty beneficial, you know, for a lot of people.

ME: A lot of privilege is built on that and a lot of things are built on that. So that shows me that it’s all the more reason to shatter it because it’s really protecting some really ugly things.

CS: Yeah. Exactly, exactly. Did you ever talk to anybody from MDA? Did you have a negotiations or conversations with them or they just didn’t touch it?

ME: They sent us a Cease and Desist Letter which is a good thing. I think every activist needs to have an arrest or some kind of something that shows they’ve been arrestesd and some kind of Cease and Desist Letter. Those are the two badges of honor. And we did get one of those. And my sister and I just basically laughed and said, “That would be great. Please let them sue two of Jerry’s kids”…

CS: (laughs emphatically)

ME: …and we will definitely make sure that we show up in court and we’ll definitely do all that. And, of course, they never did. You know, they tried to discredit us and things like that but it was, again, they ended up doing everything that we wanted them to do which was to get rid of the telethon and get rid of Jerry Lewis. It took awhile but it’s happened so we fought and fought and in the end ended up having him give in.

[Music plays briefly]

CS: So, I look at your work and your life and I think there’s sort of this physical activism that you’ve done and so many people have benefitted from it. But there’s also the activism that you do in your writing, you know, and in your conscience building, consciousness building. I don’t want to embarrass you, right, but I wanted to read what Ebert has said about you. Roger Ebert. Maybe you could talk about him. He says, “Some of the fiercest and useful satire on the web right now is being written by a man who signs himself, Smart Ass Cripple. Using a wheelchair as a podium, he ridicules government restrictions, cuts through hypocrisy, ignores the PC firewalls surrounding his disability and is usually very funny.” I thought that “usually” was good.

ME: (laughs)

CS: “Because he has been disabled since birth he uses that as a license to write things that others may think but don’t dare say.” What’d you feel when you read that?

ME: Um…flattered. (laughs) I came across him by accident because he was a friend of Marca Bristo, head of Access Living, and I wanted to interview him for Independence Today, a publication I write for. The reason I wanted to interview him in the first place was because he wrote something shortly after he was disabled called, “I’m Not Pretty Anymore”.

CS: Right. I’ve read it.

ME: And I remembered that very much and I remembered how he was not afraid to be “out”. I know a lot people would have hid or would have put on a prosthetic and tried to fake it or done a Skype or something. And he was like, “I’ve got my film festival and I’m going and if you don’t like it, screw you”. And that was great and it did a lot of good for a lot of people. So, I enjoyed that about him and that’s why I wanted to interview him. And, I guess, whatever it was that I was saying somehow spoke to his disability experience too.

CS: I think the things that he speaks so highly of or the way that he reads you or read you (past tense) is that he saw it as a real art form, this activism that you were doing. That what you were doing was not only politically important but aesthetically good. I mean, do you think of it as art? Do you think about the writing that you do as art?

ME: Well, some of it, yeah. I mean, I’ve written plays and such too so definitely I’ve done art.. But yeah, I mean it’s satire and I just enjoy satire. I think especially politically it’s very effective. I think humor gets at things that you can’t in other ways. I think humor is hard for the subject. If you’re poking at a trump type, it’s much harder for them to defend themselves against humor than it is against you listing a bunch of facts about how they did “this and that”. Well, we always try to incorporate humor into actions we do with ADAPT. Like we would go to CTA board meetings and there was a man named Michael Cardilli who was the head of the CTA and he was pretty much central casting bureaucrat, a tall guy with Italian suits. He he literally had a pinkie ring. At the time you could smoke in public and he would smoke big long cigars in the board meetings. So, I was like “Wow, we couldn’t have a better stereotype to poke fun at.” So, we showed up at a meeting once and we had name tags that said “My Name Is” and we just wrote “Cardilli” on them and we had cigars and we were mocking him. When he would smoke, we would smoke. And after awhile he figured out that we were mocking him and he stopped smoking and he got really upset. But I thought it was good for our people because they wouldn’t do that if they were afraid of him. They wouldn’t be able to make fun of him and not being afraid of him was really important because then that takes away about 99% of their power if you’re not afraid of them. So I think it was important in that way and that’s why I like to use it as much as possible. I guess the reason why I do both art and activism stuff is I’ve never quite felt comfortable, for me personally, that art was enough because I’ve always thought that if I go to the Speaker of the House and I say, “You know if you don’t stop screwing around I’m going to write a play”…

CS: (laughs emphatically)

ME: …he’s not going to be really scared about it. But if I say, “I’m going to have 20 people sit in your office”, he’s going to be a little more scared. So, I always felt that me personally that I just never felt like art was enough so I felt I had to do this other stuff too but it obviously plays a big role. It has with all kinds of other movements, but there’s no substitute. At some point you’ve just got to get people in their face some way or another either on the internet or in person. Art can be used to get people to that point but at some point you’ve just got to get in the face of the bad guys until they’re not bad guys anymore.

CS: Yeah and I suppose that’s an ongoing job.

ME: Oh yeah. New bad guys pop up.

CS: It’s never ending, right.

ME: But when I look back 30 years it is a lot different. It’s a shame some of the things some kids are still dealing with in terms of education especially and on Olmstead enforcement and things like that. It’s a shame that some of that stuff still goes on but it’s a much easier world at least to get around in physically than it was even 15 years ago.

CS: So what’s now? What do we need to fight for now? If we’ve gotten to a moment of access and we’ve gotten to this moment where at least access is better. So, you mentioned education. Are there other things that you’re looking at right now that are the sort of main issues that we all should be thinking about?

ME: Well, kind of the way ADAPT looks at things is, for instance, if you take the person who has the least; has no money, no family and is pretty much here for the community to help. What do they need first? Well, first they need to not be in an institution. So how are they not in an institution? Well, they need a place to live and they need people to help them. So, those would be, to me, the first things that you take on. Then, once they get that what’s the next thing they need? Well, they need transportation; they need infrastructure. So those would be the next things. And then after that comes jobs and education and things like that. So, people need to work on those and I’m glad they are, but I’m more interested in the things that can get and keep people out of institutions because I think not only will it benefit those if we create a place where we don’t have to worry about people being stuck in institutions then that’s better for all of us. In order to reach that point we’ve had to really radically change a culture and that’s a culture that’s going to be better for all of us. So I like to deal with the things that trap people into institutions. Those are the most important issues and the ones that I think we haven’t dealt as much with because the people that founded independent living were people that, by our definition, were people that were pretty privileged. Most of them were white and educated and had good families and they weren’t mean-spirited, it’s just not where they came from. They weren’t people trapped in institutions and I don’t think they really thought as much about that. Wade Blank who founded ADAPT is the guy who I think started digging into that the most and brought that forward. A lot of progress has been made on that but there’s still way way too many people that get stuck especially when something comes out of nowhere where they’re walking one day and not the next and they live in a 3rd floor walkup and they’ve got to be out of rehab in 5 weeks. “Well, here’s a nursing home.” That’s where you can go. Nowhere else but that’s where you can go and that’s way way still too much of that.

CS: Well, Mike, thanks. Thanks for talking, man.

ME: Alright.

CS: Keep up the good work.

ME: Thanks for the interest. Thanks for your great work over there. Definitely want to make it this year.

CS: Yeah. We’re all sort of fighting for that same thing. Just like change people’s pictures; change the imagination that people have. It’s good work. It’s hard work, but it’s good work.

ME: Yeah, it’s organizing.

CS: Exactly, exactly, cool. Thanks Mike. That’s great.

ME: Alright. Thank you.

[Rock music plays loudly then fades]

Mike Ervin, unbelievable. What a great guy. Look, if you don’t read his blog, Smart Ass Cripple, I would really encourage you to do that. That stuff is just so good. Next time on DisTopia, conversation with the amazing musician Gaelynn Lea. You might have heard of Gaelynn. She won the “Tiny Desk Concert”, NPR competition and she’s a brilliant artist. Her music will blow your mind as will her story. We’re also going to start a new segment called Caregiver Corner where people just like you can tell their stories about caregivers which can be complicated, and frustrating, and awesome all at the same time. So we’ll have Caregiver Corner as well. But, until then, DisTopia Podcast has been a production of DisArt. If you want to know more about DisArt Festival, visit DisArtFestival dot o-r-g. DisTopia is produced by Liz Waid with help from Katie Matheson and Jacob Meyer. We got musical help this week, as always, by the New Midwest and David Molinari. I’m Christopher Smit, your host. Talk to you soon.

[Rock music plays louder then fades]

Woman’s voice: Subscribe to DisTopia on iTunes and make sure to visit our website, DisTopiapodcast.org, to find transcriptions, all of our episodes, DisTopia news, and much more.

[Rock music plays loud until the end]